Hello, friends. I am musing these days on the color of khaki. One of the most striking and pleasingly historically accurate scenes in the recent film War Horse (which was great, by the way, and upon which I shall comment post-haste) was one in which a group of officers stands before the camera. Modern viewers might be surprised by the veritable spectrum of colors that they wear--olive, moss, tan, bottle green. Uniforms are supposed to be uniform, after all, aren't they? If we explore a bit, however, we find that khaki--which today might conjure up only images of dull cotton trousers sold in mass quantities by major clothing chains--has a fascinatingly, insistently, diverse identity and history.

|

| A scene from War Horse, from The Telegraph's media archive. |

The Oxford English Dictionary defines "khaki" as "Dust-coloured; dull brownish yellow, drab." The term appeared and evolved in the mid-nineteenth century, taking its roots in British Imperialist conflict/conquests in India. Early periodicals and publications describe troops "dressed in khakee [sic]," linking the shade closely to the color of dust or mud. Khaki, as it came to be spelled over the later Victorian period, was made in India, and the OED's citations of the term suggest that one of its most hallmark features was, paradoxically, its variation. An 1890s reference book on Indian products comments, in fact, somewhat desultorily, "It is needless to attempt an enumeration of all the Khaki dyes of India."

Writer Viju Mangalore has an interesting and detailed article about the history of khaki production in India, noting its roots in the southwestern city of Mangalore. The Met Museum also has a useful overview of Indian textiles made for trade.

Wikipedia notes that khaki was adopted as a uniform material and color after the 1840s; the cloth was linen or cotton, and its color came from mulberry dye. The British Army used khaki uniforms, according to Wikipedia, for foreign campaigns in the 1890s, with a more greenish, darker, shade becoming typical for "home service dress," after the turn of the twentieth century.

|

| "Why Aren't YOU in Khaki?" poster, 1915. © IWM (Art.IWM PST 5153) |

The color of khaki continued to defy conformity into the First World War. As my current dissertation research subject, Siegfried Sassoon, writes in his semi-autobiographical Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man and the subsequent Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, Army officers ordered their uniforms from tailors. The tailor's ability to locate the proper shade of khaki, however, was as varied as the cloth itself. Sassoon's fictional alter-ego notes that one man's "shirt and tie were more yellow than khaki" (MFHM, 260) and, later, that a Brigadier is a source of annoyance because of his "light-colored shirt" (MIO, 34). Variation clearly continued to dog the military leaders who sought uniformity during the Great War.

|

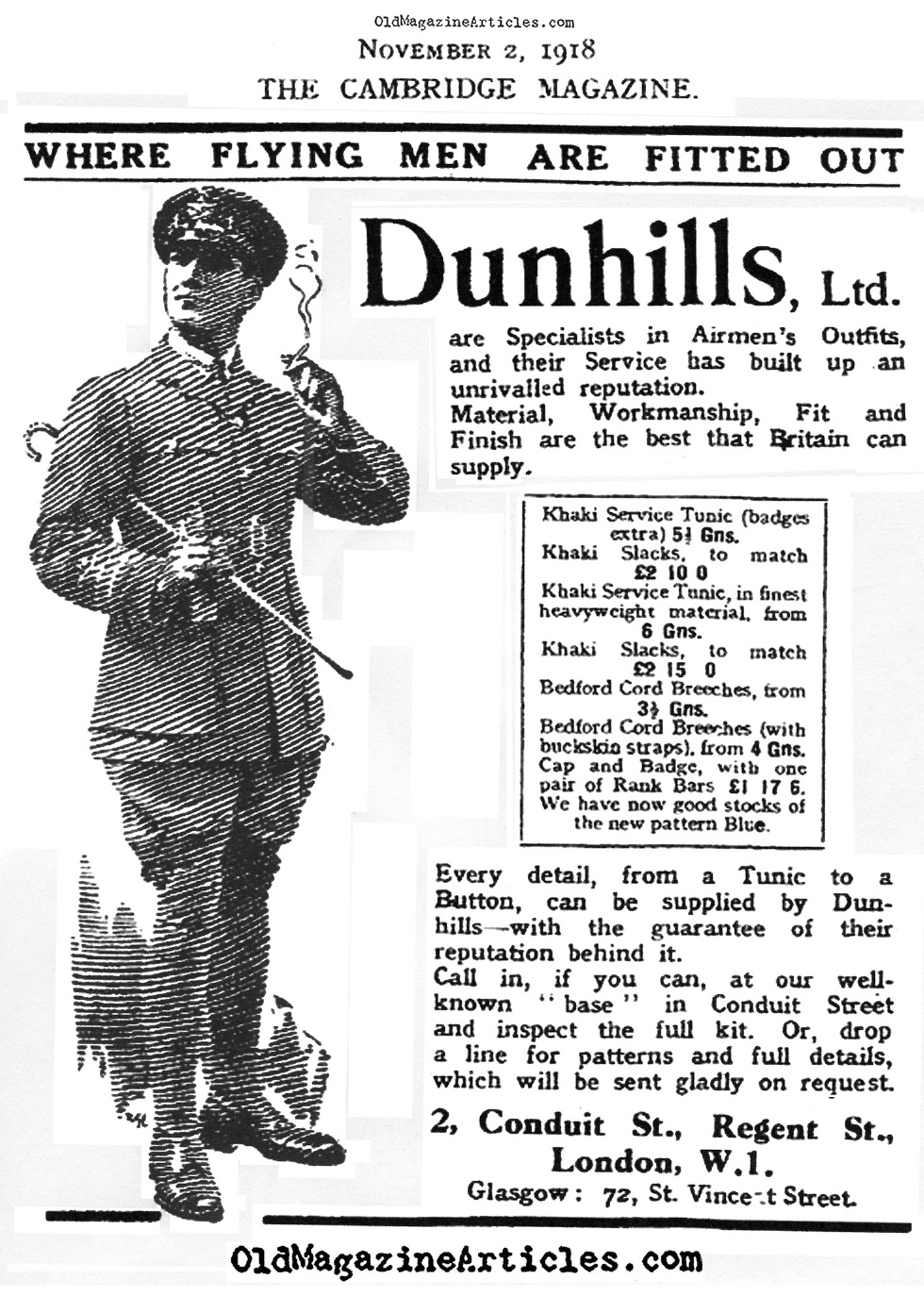

| Barely more than a week before Armistice, Dunhills Tailoring offers uniforms for "Flying Men." |

Though the color of khaki cloth is defined in dictionaries and military manuals, its real, material, form was widely varied for our ghosts of 1914. I enjoy this paradox--the appointed uniform color that refuses uniformity. Surely, however, for most soldiers and officers, the mud and dust of the trenches came to cloak that individuality with the grim evidence of service and suffering on the front. Though he notes the confounding multiplicity of khaki in his prose, Sassoon also wrote, in verse published in the 1918 collection, Counter-Attack and Other Poems of "the plastering slime," and "the sucking mud," finding, in these and other phrases, numerous ways of conveying the oppressive conditions of the trenches and battle zones, as though the mud there was active, destructive, covering over all traces of individuality, of life.

I hope that this musing allows you to consider the color of khaki--what it means to us today and what it has meant over its long history, to people in many places around the world. It is far more than just a uniform shade.

© Fiona Robinson

I hope that this musing allows you to consider the color of khaki--what it means to us today and what it has meant over its long history, to people in many places around the world. It is far more than just a uniform shade.

© Fiona Robinson

The colour of the poster seems to most closely repesent khaki - although it could be seen in all shades, i'd say the poster colour is best representative. The colour of khaki used on War Horse, especially for the normal Infantry soldiers in the 1914 scenes is way too green, and Officer's colour khaki tended to be of a more greener shade than the 'normal' Service Dress worn by the regular soldiers. Officers also provided their own uniforms, hence the various differing shades in War Horse is accurate - unlike a lot of the film!

ReplyDeleteThanks for the detailed comments. Yes, I agree that the differing shades in the officers' uniforms was a nice bit of accuracy, despite the range being a little off. Perhaps there's a dreamy sort of effect added to the scene's realization or we are seeing through the eyes of Joey the horse...It is interesting that the poster captures the most typically associated shade.

ReplyDelete