Hello dear readers,

I hope you are happy, warm, and enjoying yourselves as Christmas approaches! Here are a few amazing WWI history finds from around the web:

The IWM's Great War Centenary has a wonderful blog post with audio about the bitter winter of 1916-17. This is the same winter pictured in the photo of men having Christmas dinner in a shell hole in my last post. The photo appears at the bottom of the Centenary's blog post, along with many other vivid illustrations and artifacts from this truly dreadful winter.

I've just found the new World War One Discovery Programme, which gathers online WWI resources from all over. A phenomenal resource.

Oxford's World War I Centenary Programme has an informative blog about WWI-related events and resources (mostly in the UK).

Enjoy!

Fiona

Friday, December 21, 2012

Thursday, December 20, 2012

Christmas Across the Great Divides

|

| Weee! A soldier on leave at Epsom, 1914. © IWM, Item Q 53560. |

It's December 19th and Christmas is less than a week away! Last year at this point, I was writing about the famous 1914 Christmas Truce and about gifts for soldiers, like the Princess Mary's Gift Box. Both of these phenomena reflect the crossing of significant barriers or divides, whether that which lay between one side and the other on the battlefield or between home and front. A wartime Christmas mediated such boundaries in many ways. Christmas was a time to set aside differences, in the case of the truce, which was said to involve games of football, solemn reflections, and food and gift exchanges. It was also a particularly meaningful time for civilians to connect with troops.

|

| A.W. Ford & Co. ,"Buy a Christmas Present for Your Soldier Friend," ca. 1914-18. © IWM, Item PST 10797. |

The poster above suggests a pipe or a pouch of tobacco as a gift for a soldier, urging the shopper to make the purchase as a safeguard against forgetting a serviceperson altogether (a sad and hopefully unlikely possibility). Below, the so-called "Sheffield Telegraph" Fund was a safeguard against the absence of Christmas puddings for soldiers:

|

| "Christmas Puddings for Soldiers and Sailors," ca. 1914-18. © IWM, Item PST 10793. |

The soldiers who would have received such treats from home were not so lucky as to have been granted leave for the holiday (like their sledding comrade in the first image here). However, these men would have celebrated the holidays in as merry a fashion possible. Photographs from the IWM's collections database suggest that every effort was made to mark the occasion, even in the harshest of conditions:

|

| Christmas dinner in a shell-hole, 1916. © IWM, Item Q1630. |

I can't tell whether the group in the above photo are dining in the company of a grave (marked by the mound of gravel and wooden cross?). It certainly appears so. As I noted in my previous post about wartime theatre, many festivities on the front had to confront severe circumstances or limitations in achieving their various illusions. Regardless of whether my suspicion about the photo here is correct, the soldiers pictured are participating in a kind of theater of their own, replicating as closely as possible a festive meal shared between loved ones who are gathered specially for the occasion. Given the grim necessity of eating a surely modest supper whilst assembled in a blasted crater and possibly in the company of a dead comrade, the distance between the real and the imagined or fancifully replicated is clear, though the effort to bridge this divide is moving.

That the men keep their helmets on throughout this meal suggests that while their meal may represent a respite from the everyday reality of war, very serious danger persists. It is possible, of course, that there is no attempt to erase the battlefield here. The soldiers may well be embracing their prevailing reality (especially given their chronologically and psychologically entrenched position in the disastrous midle years of the war), with the nod to holiday tradition a somewhat farcical performance that can only highlight the impossible distance between themselves and a pre-war era or a civilian world.

Back at home, civilians seeking a bit of festive escape from the everyday might have attended the "Christmas in Wartime" event:

|

| "Christmas in Wartime," ca. 1915. © IWM, Item PST 1074. |

I hope you've enjoyed this first set of images and musings under our Great War Christmas tree this year. I'll be back with more holiday goodies leading up to the big day next week!

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

1914,

1915,

1916,

British Army,

christmas,

entertainment,

ephemera,

homefront,

IWM,

photography,

posters,

trench experience,

WWI

Saturday, December 15, 2012

India in Flanders Field: "Our Day," December 1917

|

| "Our Day" Poster, India, 1917. © IWM, Item PST 12592. |

Another almost-Christmas post for my readers today. I found this interesting poster in the IWM Collections Database this morning whilst looking for holiday-related items. It was, I discovered, a timely find. Almost exactly 95 years ago, the Red Cross's "Our Day" celebrations took place in India.

I managed to locate this digitized newspaper article (oh, how I love the internet!) about the festivities at the National Library of Australia's website. On December 13th, 1917, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that, all across India on the 12th, a fundraising effort and various Imperial huzzahs (marked by Union Jack "buttonholes," lovingly circulated "portraits of Their Majesties," etc.) were raised.

Here's another poster from "Our Day," this one more clearly linking the day's purpose to the Red Cross's fundraising in India:

|

| "Our Day" Poster, 1917, India. © IWM, Item PST 12590. |

According to the 1917 or 1918 book, The Work of the American Red Cross, which reported on efforts of the American branch of the organization as well as its international collaborations from "the outbreak of War to November 1, 1917," the "Our Day" fundraising campaign took place in many nations and was a tremendous fundraising success for the British Red Cross. Here, for instance, is a poster proclaiming a different "Our Day" in South Africa:

|

| "Our Day" poster, South Africa, ca. 1917 (?). © IWM, Item PST 12337. |

In prior years, the Red Cross had organized "Our Day" campaigns, though all indications are that 1917 was the first and/or only year of India's participation. The posters' imagery suggests an effort to make or find order amongst the chaos of the battlefield. Angelic or benevolent figures represent the Red Cross's hopeful, helpful, presence amid the pain and struggle of soldiers. The bright white light in the South African poster or the nurse's crisp apron are depicted rising above strife and focus our attention within each image. The first poster (at top) is the least similar in its imagery, though its promise that the funds collected will go primarily to the "men fighting in Mesopotamia" is supported by the various sketches of soldiers in action.

If you are moved to remember soldiers' and/or their families this holiday season, you might check out my earlier posts about service or contribution opportunities among several well-respected charities in the U.S. and Britain. For more about India's role in the Great War, take a look at earlier writings in the "India in Flanders Field" series here on "Ghosts of 1914."

Next time we'll get into the holiday spirit and begin honoring Christmas with the ghosts of 1914. To my readers celebrating Hanukkah, may you enjoy the last weekend of the festivities.

© Fiona Robinson

Friday, December 7, 2012

Great War Festivities: The Theater

Hello Readers,

© Fiona Robinson

December will be a month of festivities here at "Ghosts of 1914." While we will, of course, be looking at December holidays, I wanted to start us off with a brief consideration of some other kinds of festivities. Included in that category are the many, many, theatrical performances and events that were so vividly a part of Great War experience at home and on the front.

Theater was an important aspect of the war--entertainment for troops and civilians was an important cultural space or experience in which relaxation, pleasure, and a bit of escapism were possible. As the above photo of a Canadian performer preparing to play a female character (because women would not have been present on the front) shows us, wartime theater often worked within many limitations to achieve its illusions. While doing research on British P.O.W. camps, for instance, I discovered that imprisoned soldiers frequently participated in light-hearted theatrical shows or other entertainments. The disparity between such momentary fantasy and the horrible gravitas of a prisoner's typical existence is quite moving. Despite (or perhaps because of) grim circumstances and daily oppression, prisoners of war from many nations embraced the opportunity to set reality aside and don costumes, sing or dance, and play dramatic roles. There were politically-motivated theatrical events for P.O.W.s too. A pamphlet or flier in the IWM collection represents a German P.O.W. "production of music, recitations, and a lecture" all about William Shakespeare at a camp on the Isle of Man.

|

| Canadian performers (including a female impersonator) getting ready for a show, 1917. © IWM, Item CO 2013. |

Theater was an important aspect of the war--entertainment for troops and civilians was an important cultural space or experience in which relaxation, pleasure, and a bit of escapism were possible. As the above photo of a Canadian performer preparing to play a female character (because women would not have been present on the front) shows us, wartime theater often worked within many limitations to achieve its illusions. While doing research on British P.O.W. camps, for instance, I discovered that imprisoned soldiers frequently participated in light-hearted theatrical shows or other entertainments. The disparity between such momentary fantasy and the horrible gravitas of a prisoner's typical existence is quite moving. Despite (or perhaps because of) grim circumstances and daily oppression, prisoners of war from many nations embraced the opportunity to set reality aside and don costumes, sing or dance, and play dramatic roles. There were politically-motivated theatrical events for P.O.W.s too. A pamphlet or flier in the IWM collection represents a German P.O.W. "production of music, recitations, and a lecture" all about William Shakespeare at a camp on the Isle of Man.

Troops in service and civilians at home were also committed to the theater in wartime. There are dozens and dozens of beautiful and exciting images representing the theater of war in the IWM's wonderful collections database. Posters and artworks concerning exhibitions of war photographs, reenactments, concerts, comedy acts, and all sorts of other entertainments can be found. Just a sampling of these resources can demonstrate the wide variety of theatrical festivities that our ghosts of 1914 might have enjoyed. For example, female munitions workers watch a show in this lovely sketch by Nellie Isaac:

|

| Nellie Isaac, "At a Performance in the Canteen Theatre," ca. 1914-18. © IWM, Item ART 2318. |

An aptly-named company, "The Shrapnels," advertise their upcoming concert for British troops in a 1915 poster:

A performing troupe with a lovable though somewhat odd name, "The Merry Magnets," advertises a pleasant-sounding outdoor concert during the last summer of the war:

|

| "The Merry Magnets," 1918. © IWM, Item PST 13757. |

At home in London, the Women's Auxiliary Force advertises a multi-faceted event including a flower show, carnival, costume parade, and various musical groups to be held at the Savoy Hotel, 1918. From all indications, this was a high-society fundraiser:

|

| "Floral Fete and Carnival," 1918. © IWM, Item PST 5486. |

Thank you for joining us for this little exploration of one of the many scenes that played out on the stage of Great War history! Stay tuned for holiday-themed posts next time at Ghosts of 1914.

© Fiona Robinson

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Remember November: Sweetheart Brooches

Hello Dear Readers,

A simple post today about a particular kind of Great War artifact: the sweetheart brooch.

Above is a lovely example of a sweetheart brooch, a commonly exchanged jewelry item during both twentieth century world wars. The brooch tradition, some say, began with the Boer War, though soldiers and loved ones have exchanged various small tokens of remembrance for ages. There are, furthermore, non-military sweetheart brooches, which were popular especially in the Victorian era.

© Fiona Robinson

A simple post today about a particular kind of Great War artifact: the sweetheart brooch.

|

Sweetheart brooches are one aspect of the amazing array of insignia that civilians donned during the Great War. For example, I wrote some time ago about my own Needlework Guild Badge, a small symbolic brooch for textile volunteers. As wartime tokens of remembrance, sweetheart brooches symbolized relationships, pride, and served as a visual symbol of the constant stream of thoughts flowing between service-people and civilians. The below photograph, from the wonderful British Army Children's Archive, shows a mother and her baby. The woman, whose tightly clenched right fist (resting on her knee) and somewhat weary look seem to evidence fatigue, grief, and determination, wears a sweetheart brooch at the top center of her blouse.

|

| WWI mother and child, with mother wearing a sweetheart brooch. © TACA |

A brooch wearer like the woman above reminded others who saw her of an important relationship, though her partner or relative was absent. I like to think, furthermore, that seeing the brooch on one's own clothing in the mirror or touching it, whether with an unintentional graze of the hand or purposeful contact, was part of a sweetheart brooch's emotional "technology." Many kinds of jewelry offer such transmissions of feeling or thought, whether helping to recall memories or gather, momentarily (as when we slide a locket along a necklace or caress a wedding ring), an expansive set of emotions. Are such gestures truly absent-minded? I don't think they can be entirely...

Sweetheart brooches came in many forms, often symbolizing a soldier's regiment and marrying romantic and military imagery. The Empire to Commonwealth Project's website has the widest collection of sweetheart brooch images I could find. From around the web, here are a few other examples:

|

| WWI-era Royal Navy Sweetheart Brooch with mother-of-pearl backing. © Field Service Antique Arms and Militaria. |

|

| Silver sweetheart brooch of the Liverpool Pals, n.d. © IWM, Item INS 6139. |

I hope you've enjoyed this little excursion through one of my own favorite aspects of WWI material history. This post concludes November's month of remembrance-themed writings. Next month I'll be looking at holidays and festivities on the front and at home. Thanks for reading and stay tuned!

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

art,

badge,

British Army,

civilian life,

clothing,

ephemera,

icons,

IWM,

knitting,

popular culture,

queen mary's needlework guild,

relationships,

soldiers,

women,

WWI

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

Horlick's and the Ghosts of 1914

|

| "Horlick's Ration of Malted Milk Tablets," ca. 1914-18. © Brown University. |

Today I write in a lighter vein amid our recent attention to remembrance and commemoration. The primary theme of the month will continue, rest assured. I just couldn't help but write about a cheerier aspect of First World War history to which I recently connected.

Horlick's was something of which I'd heard in various places but had never encountered in person. Most recently, while watching PBS's excellent series, Call the Midwife, I noticed that characters in the television drama, which is set in the post-World War Two era, mentioned drinking Horlick's left and right. The show's tired, frazzled, nurses and nuns turn to the drink when agitated or exhausted. Perhaps--almost certainly?--this was deliberate product placement. However, the drink's comforting qualities (which are still celebrated today) were so frequently touted that I grew curious.

Here in America, I feel as though the range of popular non-alcoholic beverages is concentrated mostly in the carbonated category. We like our sodas (though I'm not a huge fan). Tea has some loyal drinkers, especially in my family, and coffee and its spawn of various nominally-related improvisations (usually blended and topped with assorted whipped cream, sprinkles, and syrups) are also beloved. Given this liquid landscape, beverages less well-known in the U.S., such as Bovril, Oxo, or Horlick's, for example, take on rather exotic and mysterious aspects.

You may wonder why I'm writing about Horlick's here at Ghosts of 1914. Well, as I discovered through various excursions online, Horlick's had an important role during the Great War.

Now an internationally-sold product, Horlick's had its origins in Atlantic crossings. It all began in the 1860s, when British brothers William and James Horlick moved to the United States and established a factory producing a malted milk beverage in Chicago, Illinois. After moving the company to Wisconsin and patenting their beverage powder mix, the brothers stretched the company's reach back across the pond. A London office and a manufacturing plant in Slough were established by 1910.

Horlick's became important for British soldiers on the front in World War One. As with tea-making provisions that I covered in an earlier post, Horlick's was a dried product and, formed into tablets, it could be included easily in a soldier's pack. Horlick's was known to have nutritive and calming powers. In the above poster from Brown University's collection, ambulance drivers pause to snack on the tablets directly, without even mixing them in water. The "delicious and sustaining" tablets provided important nutrients, making their consumption, as the poster's verbiage claims, "an every-day incident on the front." Though there isn't a related image, the IWM has a letter in its collection related to the procurement of Horlick's tablets for a British prisoner-of-war in Germany, in 1915.

Indian troops in the British Army became accustomed to consuming Horlick's while serving in the First World War, according to Wikipedia. This "every-day incident" led to the brand's foothold in India after armistice. By the 1920s, as historian Douglas E. Haines writes, Horlick's was advertised in India as a health product for all. The company's later promotional campaign, Haines's fascinating analysis shows, revolved around colonial-era stereotypes and depended heavily on association with masculine strength. The long and complex history of Horlick's, which persists quite powerfully and internationally today, is vaster than I can convey here. For further exploration, the company's website has some interesting resources. The LA Times also featured an informative article on the history of Horlick's some time ago.

In light of its history and near-magical claims of mood-altering properties and gastronomic enchantment, I decided recently that I simply had to try Horlick's (the UK version, which I managed to find in my local grocer's international aisle). I am sitting here drinking my very first "cuppa" as I type.

|

| Horlick's, in my beloved and historically-appropriate "Votes for Women" mug. |

And the verdict? Well...let's just say that Horlick's is going to be an acquired taste for this American. I'm not sure that I've acquired that taste based on the first try. It is a rich beverage with an extremely "nutritious" flavor, I must say. I'm not usually a malt fan, so it's understandable that my own particular tastes don't run naturally to Horlick's original. But there are always second chances and, based on the size of the tub I purchased (the only one available), there may be third, fourth, and fifth chances too, not to mention hundredth chances as well....

Anyway, it's been fun sharing a cuppa Horlick's famous beverage with you. Thanks for joining me on this little culinary detour. Next time we will return to the theme of remembrance for November.

Happy Thanksgiving to all of my readers celebrating the holiday, and stay tuned for our next visit to the Ghosts of 1914.

© Fiona Robinson

Friday, November 16, 2012

The Cenotaph Unveiled

On November 11, 1920, the Whitehall Cenotaph war monument was unveiled in London. The memorial, by definition an empty tomb, honored the staggering numbers of British war dead, nearly all of whom were buried abroad. Crowds gathered to see Edwin Luytens's impressive structure as part of the day's solemn events. As I have written earlier, attendees would later proceed to Westminster Abbey for the Unknown Warrior's funeral service.

|

| Horace Nicholls. The Cenotaph about to be unveiled, 11 Nov. 1920. © IWM, Item Q 31489. |

There are many excellent resources on the history of the Whitehall Cenotaph. Rather than retreading familiar ground, I thought I'd share a few artifacts and facts with you today. First of all, I found the following amazing newsreel about the Armistice Day 1920 ceremonies. There is footage of the Unknown Soldier's return to London as well as of King George V unveiling the Cenotaph (at 5:18):

And here is Edwin Luyten's model of the Cenotaph as envisioned after he was commissioned in June 1919 to commemorate the signing of the Peace Treaty with Germany:

|

| Edwin Luytens. Model for Whitehall Cenotaph, 1919. © IWM, Item ART 4207. |

As the IWM's detailed description for the model states, Luyten's commission to honor the Peace Treaty evolved into the Cenotaph's spartan form over the course of discussions with David Lloyd George and other government officials. Lloyd George had asked Luytens to construct a ceremonial catafalque; Luytens modified this plan to create a cenotaph instead.

Before the official unveiling in 1920, a temporary monument, designed by Luytens and constructed of wood and plaster, had stood in its place. Below is a photo of the top of the original Cenotaph. Sadly, as historian Gaynor Kavanaugh writes, the original structure, which was held in the Imperial War Museum's collections from the 1920s, was destroyed by a bomb during World War Two.

|

| Horace Nicholls. The top of the original Cenotaph, on display at the Crystal Palace, 1920-24. © IWM, Item Q 31521. |

The Whitehall Cenotaph continues to be one of London's most recognized monuments and a focal point of commemorative services each year. It was also, for a time, as I have written, a focal point for Spiritualists' haunting photography and claims about the return of the ghostly war dead.

When I visited London a couple of years ago, I remember seeing faded poppy wreaths and decorations laid at the foot of this striking and somewhat eerie structure. Many cities across the world have constructed their own cenotaphs to honor the dead of various wars. You can often find such memorials on town greens or at street crossings in communities large and small.

When I visited London a couple of years ago, I remember seeing faded poppy wreaths and decorations laid at the foot of this striking and somewhat eerie structure. Many cities across the world have constructed their own cenotaphs to honor the dead of various wars. You can often find such memorials on town greens or at street crossings in communities large and small.

|

| Horace Nicholls. Whitehall Cenotaph, 11 November 1920. © IWM, Item Q 31497. |

For more on the Whitehall Cenotaph, consult the IWM's incredibly vast resources on the monument and its history. See also Neil Hanson's book, Unknown Soldiers and Allyson Booth's wonderful critical work, Postcard from the Trenches. BBC News has a video history of the Cenotaph. See also Derek Boorman's book, At the Going Down of the Sun.

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

armistice day,

art,

Britain,

cenotaph,

David Lloyd George,

deane,

documentary,

ephemera,

film,

IWM,

memorial,

november 11th,

photography,

poppy,

remembrance,

spirit photography,

veteran,

WWI

Monday, November 12, 2012

Veterans Day: Service Ideas

Dear Readers,

Happy Veterans Day to you and "thank you" to all readers who serve, have served, or have family members in the military.

In honor of Veterans Day, here are some service ideas for you to consider. The following organizations seek donations of funds and/or needed items and volunteers.

Happy Veterans Day to you and "thank you" to all readers who serve, have served, or have family members in the military.

In honor of Veterans Day, here are some service ideas for you to consider. The following organizations seek donations of funds and/or needed items and volunteers.

This organization (highly rated by charitywatch.org) offers military families temporary "comfort housing" where they can stay locally when loved one is being treated for injuries or illness.

The British Legion provides "practical care, advice, and support" to serving military members, veterans, and families.

Operation Homefront provides emergency financial assistance to military families.

This organization advocates for healthcare, employment, and other important social services and support for veterans and their families.

Homes for Our Troops assists severely injured/disabled veterans with necessary structural and other adaptations for their homes in order to support comfortable, accessible, and independent living.

These are just a few ideas to get you started thinking about service options in your local, national, or worldwide community as you remember veterans and current military service-people.

--Fiona

Friday, November 9, 2012

Next of Kin Memorial Plaques

Hello Dear Readers,

Today I bring you some information and resources about a particular WWI-era commemorative artifact: the so-called "Next of Kin Memorial Plaque." Here is an example in the IWM's collection:

Today I bring you some information and resources about a particular WWI-era commemorative artifact: the so-called "Next of Kin Memorial Plaque." Here is an example in the IWM's collection:

|

| William Edginton Memorial Plaque. © IWM, Item EPH 2114. |

During the war, the British Government began working to develop a personalized token of remembrance to distribute to the families of fallen soldiers. Edward Carter Preston was declared the winner of a design contest held in late 1917. A paper scroll bearing an inscription penned by M.R. James, Provost of King's College, Cambridge (and an amazing writer of ghost stories) with edits proposed by King George V and the novelist Charles Keary, was also to be issued with each plaque.

|

| Memorial Scroll for Herbert Walter Stacy, 1919. © IWM, Item EPH 2223. |

The plaques were produced beginning in late 1918 in Acton and later at the Woolwich Arsenal. Scrolls were woodblock-printed at the London County Council Central School of Arts and Crafts, starting in January 1919. Each plaque bore Preston's elaborate design and each scroll the commemorative inscription; both pieces featured the individual service person's name.

It was decided that all soldiers and female service-people who died of war-related causes from August 1914 through April 1919 would be commemorated with a plaque and scroll. These materials were sent to relatives of the fallen through the 1920s. The "Great War 1914-1918"website states that over a million plaques and scrolls were created and distributed. Many are still kept by families while others are now in museum collections or in commercial circulation. The "Great War 1914-1918" website has a helpful introduction to the history of the memorial plaque, as well as many interesting illustrations. The IWM's collection also has many plaques and related objects to explore.

|

| Mounted memorial plaque and photograph for E.M. Tyler, ca. 1918. © IWM, Item EPH 499. |

While working at the Yale Center for British Art a couple of years ago, I had the honor of handling and researching the history of two sets of these remarkable mementos. They had come to the museum as part of larger family archives of items related to two soldiers. I can only say that the experience of working with these carefully preserved pieces along with their packaging and related medals, photographs, and letters was a moving experience. While nothing could bring back the dead, the plaques meant something to many families who received them and they were preserved, copied through graphite rubbings sent to friends, and displayed in loving fashion. I don't know that the plaques or scrolls could express much of the personal stories or losses that they attempted to memorialize. However, they bring home a sense--maybe only an inkling, but it's impressive enough--of the individual people who were lost in this crisis. They make the vast numbers or statistics that were part of the war's recording palpable and overwhelming at the same time. Both commemorative of a past tragedy and cautionary about the human price of combat, they help us to remember.

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

1918,

afterlife,

Britain,

civilian life,

combatant,

ephemera,

homefront,

IWM,

memorial,

remembrance,

women,

WWI

Monday, November 5, 2012

The Unknown Warrior

On November 11, 1920, the Great War was commemorated in a major way in London. Two monuments were unveiled. These were the Whitehall Cenotaph and the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey.

|

| The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior © Westminster Abbey. |

The two memorials evolved together as part of a major project to recognize the toll of the Great War and to attempt to channel public grief into some kind of symbolic object. Such projects are often fraught with difficulty and the nature of the symbols chosen and constructed are debated intensely.

The idea for Britain's Unknown Warrior (who was originally known as the Unknown Comrade, according to historian Neil Hanson's excellent book, The Unknown Soldier: The Story of the Missing of the Great War) was developed by Chaplain David Railton. Chaplain Railton first thought of the memorial when he saw the grave of an unidentified British soldier while serving in France. The grand and historic Westminster Abbey had a tradition of royalty and noted Britons being buried or memorialized onsite. Railton's "Unknown Comrade" would rest in the company of kings, queens, authors, and musicians.

Westminster Abbey's website has a detailed and very informative page on the history of the Unknown Warrior. So does the Western Front Association, whose page features several fascinating photographs. BBC News also has a useful page on the Unknown Warrior, and a fantastic, moving, slideshow of images. The Warrior's story is also recorded in the Oxford Dictionary of Biography.

The soldier who would become the Unknown Warrior was chosen from among bodies exhumed from four different battlefields on the Western Front. Brigadier General L.J. Wyatt chose one set of remains at random in a small military chapel at St. Pol in France, near Arras. The Western Front Association's page on the Unknown Warrior considers some alternate versions of the selection process.

The Unknown Warrior's body was sealed in an English-made coffin and brought to Dover aboard the H.M.S. Verdun on November 10th. Later that day, the coffin was brought by train to London's Victoria Station.

On the 11th of November, Londoners gathered for the unveiling of the Whitehall Cenotaph, which was followed by the Unknown Warrior's majestic funeral service at Westminster Abbey.

|

| S. Burgess. Napkin commemorating Cenotaph and Unknown Warrior, 1920. © IWM, Item EPH 1754. |

In the days following the service, over a million people paid their respects to the Unknown Warrior. The following year, an inscribed slab of black marble was laid over the tomb and it remains there today.

Upon the Duke of York's marriage to Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon at Westminster Abbey in 1923, the young bride placed her bouquet on the Warrior's grave. Elizabeth had lost a brother in the war and her personal gesture touched citizens across the nation. The tradition of royal brides' bouquets laid on the grave as a mark of respect continues to this day.

Though he was said to be known only by God, the Unknown Warrior offered many civilians the closest approximation to the hundreds of thousands of individual Britons known, loved, and lost in the war.

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

afterlife,

armistice day,

cenotaph,

civilian life,

icons,

IWM,

legends,

memorial,

memory,

november 11th,

relationships,

remembrance,

soldiers

Friday, November 2, 2012

Remembrance and Service

Here is a brief post, dear readers, to let you know about modern-day opportunities for remembering via service. Today's featured charity is:

The Intrepid Fallen Heroes' Fund

http://www.fallenheroesfund.org/Home.aspx

As the IFHF's Mission Statement reads,

--Fiona

The Intrepid Fallen Heroes' Fund

http://www.fallenheroesfund.org/Home.aspx

As the IFHF's Mission Statement reads,

The Intrepid Fallen Heroes Fund serves United States military personnel wounded or injured in service to our nation, and their families. Supporting these heroes helps repay the debt all Americans owe them for the sacrifices they have made in service to our nation. They are, in the words of our founder, the late Zachary Fisher, “our nation’s greatest national resource,” and they deserve all the help that our nation can provide. The Intrepid Fallen Heroes Fund is a leader in meeting this important national mission.

This charity serves American and British military personnel, focusing on severely injured veterans. They offer aid and medical rehabilitation to many servicepeople, including those with traumatic brain injuries.

The IFHF is highly rated by www.charitywatch.org , the American Institute of Philanthropy's watchdog website (and a valuable resource in and of itself).

Today's featured charity is just one option for remembering our veterans. I am not affiliated with this organization and merely offer it for your consideration and for you to find out about some of the innovative treatments and help being offered to today's injured servicemembers.

In future posts, I'll be mentioning volunteer opportunities and other charities connected to veterans, primarily in the U.S. Please feel free to contribute suggestions in comments! I'll also be back to write more about commemoration in the post-Great War era throughout the month.

--Fiona

10,000 views!

Just a quick post to note a milestone for Ghosts of 1914: 10,000 views!!

Here's to another 10,000 and another! Thank you for reading!

Cheers,

Fiona

Here's to another 10,000 and another! Thank you for reading!

Cheers,

Fiona

Thursday, November 1, 2012

November: A Month to Remember

Dear Readers,

With these thoughts in mind, posts this month will focus on the theme of commemoration as it relates to the Great War, something that figured prominently in my (recently-completed) dissertation. I will also be posting information about remembrance-related service opportunities and resources for readers to consider. I am not professionally affiliated with any organization, so my suggestions will just be ideas that I've come across and want to pass along. Feel free to contribute your own in comments.

Thank you for reading and stay tuned for more about remembrance and the Ghosts of 1914.

© Fiona Robinson

I hope you had an enjoyable Halloween and that autumn is being kind to you. Now that we've moved into November (this year seems to be going by so quickly!), Ghosts of 1914 will feature a special theme. Which is...

|

| Horace Nicholls. Whitehall Cenotaph, London, shortly before its unveiling Nov. 11, 1920. © IWM. Item Q 31488 |

Remembrance

November, the month of Armistice and Veterans' Days, is an apt time to reflect on war and peace and to be grateful for those who have served. It is a time to think of military personnel who have been lost in past and present conflicts and to consider helping their comrades who have returned home. Remembrance is not just about nostalgia and it does not necessarily involve an extended backward glance into history. We can remember right where we are, in our own communities, and we can make remembrance an act of service.

With these thoughts in mind, posts this month will focus on the theme of commemoration as it relates to the Great War, something that figured prominently in my (recently-completed) dissertation. I will also be posting information about remembrance-related service opportunities and resources for readers to consider. I am not professionally affiliated with any organization, so my suggestions will just be ideas that I've come across and want to pass along. Feel free to contribute your own in comments.

Thank you for reading and stay tuned for more about remembrance and the Ghosts of 1914.

© Fiona Robinson

Monday, October 29, 2012

War Poems for Halloween

|

| "A Jolly Hallow-e'en" Vintage Postcard, ca. 1910. © NY Public Library Picture Collection. |

Winifred M. Letts's Hallow-e'en and Poems of the War is widely available online for those of you would like to delve a bit into Halloween and Great War history.

Letts, born in 1882, was of English and Irish heritage. She was also a versatile writer, penning novels, poems, plays, and children's fiction over her career.

The Halloween-themed poems in Letts's collection are touching, rather tragic, musings. They offer an older-world vision of Halloween as a holiday when the spirits of the dead might return to familiar places and people. "Hallow-e'en 1915," for example, is an emotional appeal to the war dead, hoping that they will be drawn by the welcoming lights of home. Hearth fires, stars, lanterns, and lamps are all described as beacons for the "well-beloved dead."

O men of the manor and moated hall and farm

Come back to-night; treading softly over the grass;

The dew of the autumn dusk will not betray where you pass;

The watchful dog may stir in his sleep but he'll raise no hoarse alarm.

--Winifred M. Letts, "Hallow-e'en 1915," (5-8)Other pieces of note in this great collection are "The Deserter," a well-known piece that considers the plight of those too fearful to fight, and "A Sister in a Military Hospital," about nurses much like those whose uniforms might inspire a costume or two, as I have written previously.

Letts's book connects Halloween to the First World War in an unexpected way, offering a different perspective on the holiday than the one we might know today. In her poems, mingling with ghosts on "Hallow-e'en" is a longed-for reunion rather than a spooky thrill. Most importantly, however, Halloween is for Letts, as it remains today, a time of possibilities, a brief night when real and unreal can come together and a slightly different, more magical, world appears.

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

afterlife,

Britain,

civilian life,

communication,

ephemera,

halloween,

poets and poetry,

women,

WWI

Monday, October 22, 2012

What to Wear to War: A Nurse's Halloween

Hello Dear Readers,

Taking things to an even more intrepid level, the National Library of Scotland has some great images of two women who served directly on the front line as nurses and ambulance drivers:

Today I'm celebrating the first birthday of Ghosts of 1914! I'm delighted to have kept the wheels turning on our journey into Great War history. Thank you for joining me along the way!

I'm also sitting here on a rainy Monday thinking about Halloween costumes. I love historical costumes of various kinds and I'm determined to put my sewing skills to work at making a flapper dress at some point. I made one a couple of years ago and loved it, but this next time around I'd like to make more of a Robe de Style, which was a transitional style somewhere between the lighter post-Victorian gowns of the late 1910s and the remarkably daring ones of the Jazz Age. Here are two lovely examples of the amazing Jeanne Lanvin's Robe de Style in the Met Museum's collection:

|

| Jeanne Lanvin. Robe de Style, 1924-25. © Metropolitan Museum, New York. |

For those of us who love historical costume related to the Great War, furthermore, there are plenty of ideas. Last year, I wrote a bit about various uniforms, including that of the British (V.A.D. or Red Cross) nurse. In a pinch, a respectable replica could be whipped up from a long grey cotton dress or skirt with a collared shirt, a simple white apron (with optional red cross painted or sewn on), some white cuffs (for instance snipped from the sleeves of a worn-out t-shirt), and a deftly tied white headscarf. For example, from a nifty article on the UK Red Cross's blog, here is one of Britain's most famous WWI nurses, Vera Brittain, in uniform:

|

| Vera Brittain, ca. 1915-18. |

|

| Mairi Chisholm (?), Nurse, ca. 1914-18. © NLS, Acc 8006 (i). |

Mairi Chisholm and Elsie Knocker were, according to the National Library (NLS), the only two women permitted to serve on any Western Front battlefield. Explore the NLS's "Women in the First World War" learning site to find more details about these remarkable ladies and some of their peers. As for a Halloween costume, Mairi's trench coat and waders/high boots, as well as her messenger bag and helmet, could be replicated with modern finds and would make for a really exciting innovation on the standard nurse's uniform.

Well, I'll close for now, but there are a couple of ideas for Great War-inspired costumes that can easily be constructed out of items you may have in your own closet or that can be found at the local thrift store, army/navy supply, borrowed, or purchased inexpensively elsewhere. For more on First World War costumes, take a look at my earlier posts on this topic. And, I will be back to suggest even more ideas before the big holiday arrives!

Till later,

Fiona

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

1914,

1918,

British Army,

clothing,

dress,

photograph,

trench experience,

uniform,

waders,

women,

WWI

Thursday, October 11, 2012

On a Professional Note...

Hello again readers,

Because yours truly just finished her dissertation, it is now time for me to look for a job!

For interested parties, my professional portfolio site, otherwise known as "The Bookish Writer," is now live at:

http://bookishwriter.wordpress.com/

If you are in need of a writer, museum assistant, editor, researcher, teacher, or publishing associate, please let me know!

Cheers,

Fiona

Because yours truly just finished her dissertation, it is now time for me to look for a job!

For interested parties, my professional portfolio site, otherwise known as "The Bookish Writer," is now live at:

http://bookishwriter.wordpress.com/

If you are in need of a writer, museum assistant, editor, researcher, teacher, or publishing associate, please let me know!

Cheers,

Fiona

Hello again!

Hello dear readers,

I am back from the time warp that was submitting and shipping my dissertation! What a whirlwind the last month has been. And there's no rest for the weary. Between a short-term writing gig and some other projects and what-not these days, I am a busy little bee.

I just wanted to pop in here to let you know that, though I may have finished the biggest academic project I've yet done, a culmination of the ten or so years I've spent thinking about and working on the First World War since college, the Ghosts of 1914 are still with us--and me.

In the days after I turned in the dissertation, when everyone was saying, "you must be so relieved!" and "now it's time for a rest!" I'd nod, smile, and then think, "I sure wish I felt relieved and/or restful..." There are reasons for my lack of celebratory insouciance. Of course, handing in a dissertation is not the end of that particular process--there are numerous reviews that must take place before a degree is awarded. Waiting is the name of the game now. And, like many young academics in my position, I'm at a point between education and career when the next (professional) chapter is yet to be written and leaving the safe, structured, world of grad school (though it has its tribulations, of course) is thus a difficult prospect. Finally, the truth of having "finished" the last and most pivotal requirement of graduate school takes a long time to sink in.

Anyway, when one is at such a crossroads, it can be tempting to look, with a sudden flash of gleeful spite, at the books and papers that have set up shop in one's home and life--on desks, bookshelves, floors, bookbags, etc.--over the last several years and begin gathering, flinging, discarding, banishing...you get the idea. I've known the pleasure of returning literally hundreds of library books and throwing out old drafts, and I've imposed mental quarantines forbidding certain authors or topics at such moments in the past.

However, I haven't really felt this urge this time around. Perhaps it's all still too new. But, I think there's another--better--reason. When I look at my bookshelves, I realize that my copies of Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Vera Brittain, Siegfried Sassoon, Helen Zenna Smith, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and so many others are old friends. Furthermore, I am still curious about so much of Great War history, culture, and arts. I still have so many questions and I can sense that there are so many stories that still need to be recovered from this moment in time.

While the climb was burdensome at times, I've gotten to the top of Dissertation Mountain and I can say that the view is dazzling. It's not entirely clear what all lies before me, but I do know that there is much more to explore. I've got WWI projects already up my sleeve, to be sure--more research I'd like to do, more writing (both academic and non-) I will do. And Ghosts of 1914 is definitely here to stay. This blog has been a delight and a source of support during the last year. Here, I've had the joy of pursuing detours and by-roads in WWI history and knowing that a community of readers joins me in my explorations.

Thank you for reading and do stay tuned. In the next weeks, I'll celebrate the first birthday of Ghosts of 1914 with plenty of new posts. It's good to be back.

Cheers,

Fiona

© Fiona Robinson

I am back from the time warp that was submitting and shipping my dissertation! What a whirlwind the last month has been. And there's no rest for the weary. Between a short-term writing gig and some other projects and what-not these days, I am a busy little bee.

I just wanted to pop in here to let you know that, though I may have finished the biggest academic project I've yet done, a culmination of the ten or so years I've spent thinking about and working on the First World War since college, the Ghosts of 1914 are still with us--and me.

In the days after I turned in the dissertation, when everyone was saying, "you must be so relieved!" and "now it's time for a rest!" I'd nod, smile, and then think, "I sure wish I felt relieved and/or restful..." There are reasons for my lack of celebratory insouciance. Of course, handing in a dissertation is not the end of that particular process--there are numerous reviews that must take place before a degree is awarded. Waiting is the name of the game now. And, like many young academics in my position, I'm at a point between education and career when the next (professional) chapter is yet to be written and leaving the safe, structured, world of grad school (though it has its tribulations, of course) is thus a difficult prospect. Finally, the truth of having "finished" the last and most pivotal requirement of graduate school takes a long time to sink in.

Anyway, when one is at such a crossroads, it can be tempting to look, with a sudden flash of gleeful spite, at the books and papers that have set up shop in one's home and life--on desks, bookshelves, floors, bookbags, etc.--over the last several years and begin gathering, flinging, discarding, banishing...you get the idea. I've known the pleasure of returning literally hundreds of library books and throwing out old drafts, and I've imposed mental quarantines forbidding certain authors or topics at such moments in the past.

However, I haven't really felt this urge this time around. Perhaps it's all still too new. But, I think there's another--better--reason. When I look at my bookshelves, I realize that my copies of Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Vera Brittain, Siegfried Sassoon, Helen Zenna Smith, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and so many others are old friends. Furthermore, I am still curious about so much of Great War history, culture, and arts. I still have so many questions and I can sense that there are so many stories that still need to be recovered from this moment in time.

While the climb was burdensome at times, I've gotten to the top of Dissertation Mountain and I can say that the view is dazzling. It's not entirely clear what all lies before me, but I do know that there is much more to explore. I've got WWI projects already up my sleeve, to be sure--more research I'd like to do, more writing (both academic and non-) I will do. And Ghosts of 1914 is definitely here to stay. This blog has been a delight and a source of support during the last year. Here, I've had the joy of pursuing detours and by-roads in WWI history and knowing that a community of readers joins me in my explorations.

Thank you for reading and do stay tuned. In the next weeks, I'll celebrate the first birthday of Ghosts of 1914 with plenty of new posts. It's good to be back.

Cheers,

Fiona

© Fiona Robinson

Monday, September 17, 2012

CWGC: Forever India

I am deep in the mire of the dissertation trenches...No time to write much, as my submission deadline approaches in just two weeks! However, I did find this fascinating resource, one of many on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, that I wanted to share with you:

"Forever India"

http://www.cwgc.org/foreverindia/

Please enjoy the riches of the "Forever India" web resource, full of information about the service and sacrifices of Indian citizens during the Great War. I will be back soon for more extensive forays into WWI history with you.

Cheers,

Fiona

"Forever India"

http://www.cwgc.org/foreverindia/

|

| Unidentified image of two Indian soldiers and a tiger, not dated. Copyright 2012, CWGC. |

Cheers,

Fiona

Labels:

1914,

1918,

British Army,

civilian life,

colonial,

combatant,

dissertation,

india,

IWM,

memory,

military,

popular culture,

WWI

Thursday, September 6, 2012

Searchlights

|

| T.B. Meteyard. "Searchlights Over London," 1917. © IWM (Art.IWM ART 17172) |

The peak of Dissertation Mountain is within sight! It will be a few weeks before I'm done, but I'm getting there. Thank you for reading!

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

Britain,

civilian life,

dissertation,

IWM,

technology,

WWI

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

A Trek on Dissertation Mountain

I am quite busy these days with dissertation writing. The good news is that I have, technically, written all of the chapters. The less than wonderful news is that I have a lot of revisions to finish. And that means that the next several weeks will be spent, in large part, obsessing about Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Vera Brittain, Siegfried Sassoon, and their literary friends and relations. When I feel overwhelmed at having to climb--or keep climbing--what I call Dissertation Mountain, I just think of myself as Issa's snail, tracing one little silvery dash behind him at a time. Mount Fuji can be climbed, even if slowly. And so can Dissertation Mountain.

|

| Dora Carrington. Lytton Strachey, 1916. ©.NPG 6662 |

Another thing I do when I feel overwhelmed or disenchanted with this mountain of my making is to watch movies that have to do with my subject(s) or their time period while I work. It helps immensely to have the pleasant, undemanding, company of a familiar film while one types, deletes, has revelations, despairs, and returns to typing once again. One letter, one word on the blank page at a time, a veritable and virtual Mount Fuji slowly covered with the silvery snail tracks of my writing. The most important thing is to keep going!

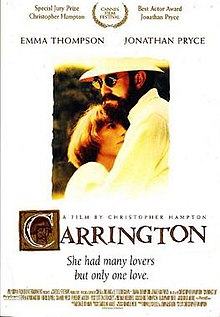

My film of choice right now is one of my all-time favorites. I've been in love with it since I first saw it over ten years ago, as part of a spectacular Bloomsbury art show at the Yale Center for British Art. I've watched it time and again and even used it in a course I taught at Yale about Bohemians in literature from Shakespeare to Kerouac. It is Carrington. Now, Michael Holroyd's Lytton Strachey and Gretchen Gerzina's Dora Carrington: A Life offer many more details than any film could provide about the lives of the two incredible figures portrayed. However, if you are a Bloomsbury fan, a twentieth-century enthusiast, a (secret) Bohemian, a fashion history person, a literature and/or art scholar, or a period drama film-lover, then do watch this movie.

|

| Carrington (1995) |

I recall being annoyed when my own copy of Holroyd's Strachey arrived a few years ago, with the image of the film's stars as Strachey and Carrington emblazoned on its cover. As a rule, I do not approve of film posters as book covers or endorsements from modern authors on classic texts (among other things). But, much as I might not have liked receiving the Carrington-decorated copy of this beautiful biography, I do love this film. There are many reasons why I enjoy it so much. Sparing myself (and you) from too many of them, it's one of my favorites because it is about real people, an era, and art and writing in which I'm interested and, more broadly, because it's about human relationships that defy standard categories but are defined--wildly and genuinely--by love.

Enough, already. I must pack up this little encampment and seek higher ground on Dissertation Mountain. I hope you enjoy the film, the two biographies, or, if you are a fellow graduate student or writer or anyone with a mountain-like project in front of you, I hope that you can be inspired to keep climbing--but slowly, slowly!

Labels:

art,

biography,

bloomsbury,

Britain,

conscientious objectors,

eminent victorians,

film,

icons,

painting,

popular culture,

relationships,

strachey,

women,

WWI

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

The Great War at the Movies

|

| Still from Abel Gance's 1919 J'Accuse. © SF Silent Film Festival Blog |

I've been dreaming of the silver screen lately, and I wanted to compile an initial list of essential films about the First World War. There are lots, of course, and many movies feature unexpected links between a primary storyline and the war. Perhaps because I spend so much time reading and writing about the war, these links pop out at me--sometimes surprising me in films I've seen many times before. For instance, the 1992 Chaplin, a favorite of mine for several reasons, includes a phase of the silent star's life when, as he travels in Britain after the war, the relevance of his art is questioned in light of the devastation that his native country has experienced. Chaplin actually made a war "comedy" in 1918, called Shoulder Arms, about which Chris Edwards writes quite eloquently at his blog, Silent Volume. I have not seen the film, but Edwards writes that the Little Tramp character enlists in the American army. Perhaps this alignment, though surely stemming from Chaplin's association with American film studios, allows the film's (strangely chosen) comedy to avoid representational contact with British experience of the war. Though comedy was not an unknown note in this experience or its expression, it is true that the film may strike viewers as odd or somewhat disorienting in its unreal depictions.

Here are ten films, to start. These are my personal picks for today, not all well-known or widely-recognized as war films, but the ghosts of 1914 haunt them nonetheless. Sometimes the most moving encounters with the Great War on film are not in movies directly about the war, after all.

1. J'Accuse (1919) Clips from this incredible film can be found here.

2. All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

3. War Horse (2011)

4. A Very Long Engagement/ Un long dimanche de fiancailles (2004)

5. Chariots of Fire (1981)

6. Paths of Glory (1957)

7. Joyeux Noel (1995)

8. Fairy Tale (A True Story) (1997)

9. Gallipoli (1981)

10. The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain (1992)

I hope you enjoy watching or remembering some of these films. Take a moment to consider the ways in which the ghosts of 1914 appear in these and other movies--at times manifesting right before our eyes, and at others, hovering at the edges of the screen.

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

1914,

1918,

afterlife,

Britain,

British Army,

combatant,

entertainment,

film,

horse,

legends,

popular culture,

technology,

war horse,

WWI

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

Updated Look

Hello Readers,

The four images that I chose depict Indian troops in formation, the devastated Verdun, France, British officers at lunch among wreckage, and British soldiers arriving in Lille. Officially, I would like to credit all four photos as belonging to:

Great War Primary Document Archive: Photos of the Great War - www.gwpda.org/photos

Take some time to explore this wonderful archive, which features historic documents as well. Occasionally, I will change the header images to show more of the ghosts of 1914.

© Fiona Robinson

A quick post to mention our slightly spruced up look, now with a title block of images from the fantastic "Photos of the Great War" World War One Image Archive. The archive features public domain photographs depicting many aspects of the Great War, from battlefields to troops of various nations, to iconic military figures.

The four images that I chose depict Indian troops in formation, the devastated Verdun, France, British officers at lunch among wreckage, and British soldiers arriving in Lille. Officially, I would like to credit all four photos as belonging to:

Great War Primary Document Archive: Photos of the Great War - www.gwpda.org/photos

Take some time to explore this wonderful archive, which features historic documents as well. Occasionally, I will change the header images to show more of the ghosts of 1914.

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

colonial,

combatant,

photograph,

photography,

portraits,

soldiers,

trench experience,

WWI

Monday, July 30, 2012

Olympic Spirit

A largely musing post today to consider the Olympics, as the 2012 London Summer Games are underway.

Of course, it is not the case that nothing else really matters or exists--this is not the reality that the Olympics, or a film like Chariots of Fire, reflect. Rather, they offer an important reminder that, in spite of all else that does matter and affect us, in our daily lives or on a global scale, transcendence is possible. Regardless of our personal athleticism (or our possession or lack of a cable television subscription), we all have access to this truth.

© Fiona Robinson

Not being a subscriber to cable television and sadly unable to obtain a digital signal for the local station's broadcast (few in my region of the San Francisco Bay Area are able to do so), I've been more or less out of the loop on the 2012 Olympics so far, with the exception of newspaper articles, a fleeting glimpse of the Opening Ceremonies online, and a bit of time spent watching swimming and gymnastics events with family last night.

What I love about the Olympics is the ideal of common humanity and the celebration of athleticism in so many forms that the Games bring us every four years in Winter and Summer.

For our ghosts of 1914, there were no Olympic Games during the war. After 1912's Games in Stockholm, Sweden, the 1916 Olympics, which had been scheduled prior to the war to take place in Berlin, Germany, were cancelled. The war cast a huge shadow over the Games, one that did not lift until the 1920 Antwerp, Belgium Summer Olympics. This Olympiad was awarded to the war-torn city as a way of initiating a healing process after Armistice. However, it appears that considerable tension remained, and several nations (including Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, and Turkey) were not invited to participate.

On a lighter note, I found that the 1920 Games included medals for Tug-of-War, which I had not previously realized was an Olympic sport! Tug-of-War lasted from 1900-1920 at the Olympics.

| ||

| The Swedish Team engaged in Tug-of-War at the 1920 Games. © Getty Images |

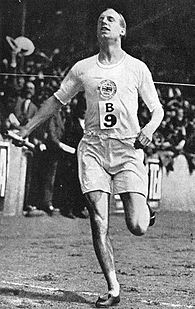

Thinking about the Olympics as having some healing power after the international crisis of the First World War brings to my mind one of my (top two or three) favorite films: 1981's Chariots of Fire (for interested parties, the film has been re-mastered and re-released in time for the 2012 Games). Depicting the story of the British runners who went to the 1924 Paris Olympics, this film captures one of many pivotal moments in Olympic history. Chariots of Fire opens with scenes of solemn memorial--a contemporary funeral service gives way to memories of 1920s Cambridge, where young men just entering the University pay homage to other young Cambridge men, just a few years older than themselves, who have died in the war. Another sequence shows us two war veterans, one with an extensive facial prosthetic, helping two future members of the Olympic team into a cab as they arrive to begin their University education. The two veterans look resentfully at their only slightly younger peers, considering the toll they have paid so that these more privileged (both in age and presumably in financial status) men can enjoy the civilian life, saved by time and circumstance from the realities of the Front.

|

| Eric Liddell at the 1924 Games. |

While it recognizes the still-painful historical context of a post-war Olympiad, Chariots of Fire celebrates the more universal Olympic ideals of athleticism, teamwork, and personal triumph over various challenges. When we watch the runners sprinting around the track or racing along a windy beach, there is something compellingly pure about their movement and their engagement with their sport--it is as though nothing else exists and nothing else matters.

|

| Harold Abrahams, ca 1924. |

© Fiona Robinson

Labels:

armistice,

civilian life,

combatant,

film,

homefront,

icons,

legends,

memorial,

memory,

olympics,

peace,

prosthetics,

remembrance,

sports,

WWI

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)