Not being a subscriber to cable television and sadly unable to obtain a digital signal for the local station's broadcast (few in my region of the San Francisco Bay Area are able to do so), I've been more or less out of the loop on the 2012 Olympics so far, with the exception of newspaper articles, a fleeting glimpse of the Opening Ceremonies online, and a bit of time spent watching swimming and gymnastics events with family last night.

What I love about the Olympics is the ideal of common humanity and the celebration of athleticism in so many forms that the Games bring us every four years in Winter and Summer.

For our ghosts of 1914, there were no Olympic Games during the war. After 1912's Games in Stockholm, Sweden, the 1916 Olympics, which had been scheduled prior to the war to take place in Berlin, Germany, were cancelled. The war cast a huge shadow over the Games, one that did not lift until the 1920 Antwerp, Belgium Summer Olympics. This Olympiad was awarded to the war-torn city as a way of initiating a healing process after Armistice. However, it appears that considerable tension remained, and several nations (including Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, and Turkey) were not invited to participate.

On a lighter note, I found that the 1920 Games included medals for Tug-of-War, which I had not previously realized was an Olympic sport! Tug-of-War lasted from 1900-1920 at the Olympics.

| ||

| The Swedish Team engaged in Tug-of-War at the 1920 Games. © Getty Images |

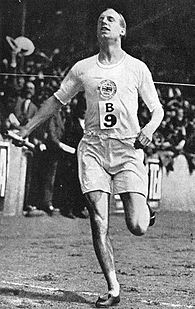

Thinking about the Olympics as having some healing power after the international crisis of the First World War brings to my mind one of my (top two or three) favorite films: 1981's Chariots of Fire (for interested parties, the film has been re-mastered and re-released in time for the 2012 Games). Depicting the story of the British runners who went to the 1924 Paris Olympics, this film captures one of many pivotal moments in Olympic history. Chariots of Fire opens with scenes of solemn memorial--a contemporary funeral service gives way to memories of 1920s Cambridge, where young men just entering the University pay homage to other young Cambridge men, just a few years older than themselves, who have died in the war. Another sequence shows us two war veterans, one with an extensive facial prosthetic, helping two future members of the Olympic team into a cab as they arrive to begin their University education. The two veterans look resentfully at their only slightly younger peers, considering the toll they have paid so that these more privileged (both in age and presumably in financial status) men can enjoy the civilian life, saved by time and circumstance from the realities of the Front.

|

| Eric Liddell at the 1924 Games. |

While it recognizes the still-painful historical context of a post-war Olympiad, Chariots of Fire celebrates the more universal Olympic ideals of athleticism, teamwork, and personal triumph over various challenges. When we watch the runners sprinting around the track or racing along a windy beach, there is something compellingly pure about their movement and their engagement with their sport--it is as though nothing else exists and nothing else matters.

|

| Harold Abrahams, ca 1924. |

© Fiona Robinson