I love cats (my own beautiful Rosie most of all, naturally). So, I thought that for today's post I would take a look for cat-related items in the

IWM's wonderful database. I found the above charming poster of folktale hero Dick Whittington marching to the war with his impressive black cat, helmeted and walking magisterially on hind legs, at his side. Dick looks cheerfully at the viewer, tipping his hat to us as he lugs his considerable load of equipment. The cat, however, keeps eyes forward, pointing his body and gaze ahead of him, focused on their destination.

I must break from Great War talk briefly to mention that I keep thinking of

AMC's Mad Men every time I see the name "Dick Whittington." The name sounds much like the real name of the show's 1960s protagonist Don Draper. Don, we eventually learn, is really Dick Whitman, whose name, history, family, and dead-end future he sheds (subsequently claiming the real Don Draper's name and identity from a dead comrade) while serving in the Korean War.

I do hope I haven't ruined any mysteries for Mad Men followers out there, though the Don Draper/Dick Whitman storyline was revealed at least a couple of seasons ago, if not more. I digress, however. This is not a television blog; the bottom line is that:

Dick Whitman & Dick Whittington=no relation

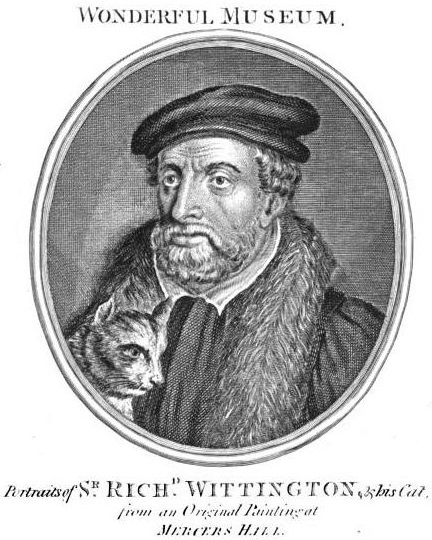

Since we are talking about identities false and true, though, who was the "real" Dick Whittington? The character comes from an old English folk tale loosely based on the true story of

Richard Wittington, who served as Lord Mayor of London in the 1300s. Wittington's legend lived on into the twentieth century and came to inspire Arthur

Cary to create the poster above in 1918. Having been

transformed into a play as early as the seventeenth century and a pantomime stage show in the early 1800s (the first version of

which starred the famous clown

Joseph Grimaldi), the story of "Dick Whittington and His Cat" was well-known to readers and theater-goers in Britain throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries.

Dick Whittington, in his fictional manifestation, is a poor boy who, through the incredible ratting powers of his cat, wins fame and fortune, eventually becoming the mayor of the great city of London. His real counterpart, Richard Whittington, is not known to have had a cat, though a source on Wikipedia

speculates that a mistranslation might have led to the appearance of the mythical animal.

A final detail worth pondering in Arthur Cary's poster is the "ET 70"

milestone that appears at bottom right. I will assume that this indicates Etaples, the northern French location of a major British base camp. Famously, the Etaples site was the setting for a

serious mutiny incident in September, 1917. Poor morale among troops led to an uprising over the arrest of a soldier from New Zealand. Military police fired into a surging crowd, killing one soldier and wounding a French civilian. Protests ensued and hundreds of men held demonstrations and eventually marched through Etaples over the next few days. When order was forcefully reestablished, punishments including one death sentence, imprisonment, and strippings of rank, were meted out. The Etaples Mutiny was a tragedy all around.

Are Dick Whittington and his cat headed for Etaples? Given the 1918 date of the poster, the Mutiny had surely made some news by the time of Cary's work. It is not clear what the two characters' march towards this location, if this is indeed where they are headed, might mean, though. Perhaps they are simply moving towards the base camp where many British troops were sent before going to the front. Or, are they signalling some solidarity with the frustrated marchers who walked through the town in 1917? A final grim possibility might be that Whittington and the cat are headed to Etaples to enforce order and subdue the spirit of unrest and agitation. No matter their purpose, Whittington appears quite boyish here as he greets us with a confident smile, and though his outfit is of a vaguely military green hue, its clearly antiquated style does not suggest that he is ready for war. His cat, though, seems possessed of a different and thoroughly modern sort of seriousness and motivation.

|

| Herbert Hiller, "'Mowler,' One of Our Mascots," 1915. © IWM, Item Art.IWM ART 4378 | | | | | | | | |

The ghosts of 1914 had their allegiances to service animals of many kinds. Horses, dogs, birds, and cats facilitated transportation, communication, safety, and even simply comfort for their human comrades. Herbert Hiller's "Mowler," pictured above, looks quite a lot like Dick Whittington's cat--wise with understanding and intent that we humans can only imagine. This crouching creature, whose glance projects feline accusation as only cats are capable of expressing, reminds us that the war was seen through many eyes and from many perspectives. The actual and the mythical proportions of the conflict, though they shift and startle us even now, take on a new dimension when we consider the feline ghosts of 1914.

© Fiona Robinson